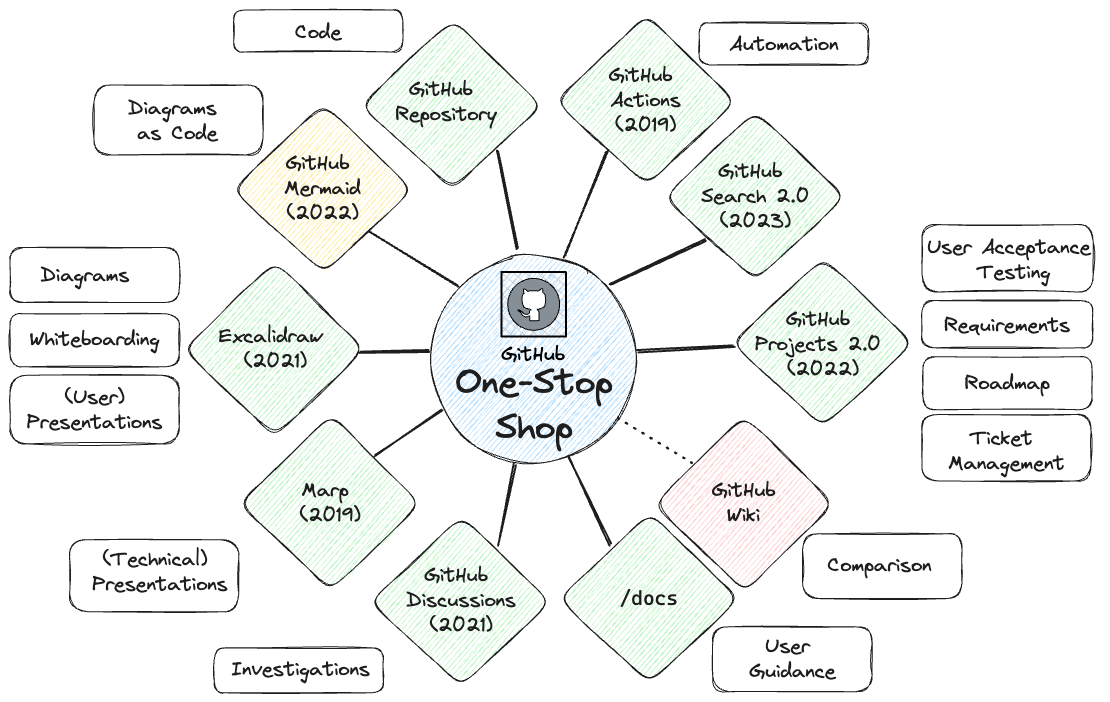

GitHub as a one-stop shop

Many people will be familiar with a development environment setup where they use GitHub repositories to store and manage code, but rely on a plethora of tools for creating and managing all other project outputs. While each tool can be very effective in its own right, this often leads to scattered deliverables, causing confusion and an increased risk of inconsistency. In this post, I outline how to consolidate all your project artefacts on GitHub by leveraging GitHub and open-source tools:

- GitHub Actions for automating software workflows

- GitHub Projects for planning and tracking work

- GitHub Discussions for documenting discovery work and communicating with users

- GitHub Pages for hosting static websites

- A

/docsfolder for documenting user guidance and technical concepts in Markdown - Mermaid for creating simple diagrams using Markdown-like syntax

- Excalidraw for creating editable diagrams and whiteboard sketches, which can be saved as code in a

/docs/imagesfolder - Marp for creating slide decks in Markdown, which can be saved as code in a

/docs/slidesfolder

These suggestions are summarised in the Excalidraw whiteboard below. Clicking on the diagram will import it into the Excalidraw web editor, where you can access links to examples from the MoJ.

Note that the post includes recommendations on how to use these tools as of February 2024. For more detailed and up-to-date instructions, please refer to the links provided.

But first, why store everything in GitHub?

Compared to your existing setup, the tools discussed in this post may offer fewer features and require a steeper learning curve. Additionally, clear migration paths may be lacking, making it challenging to switch platforms.

However, there are several advantages which I feel make it worthwhile, especially if you’re starting from scratch.

Searchability

Having all your code, tickets, documentation, and slides in one place makes it super easy to search through everything, if you can find it. Unfortunately, GitHub search used to be very limited (you can read why in the history of code search at GitHub). Thankfully, GitHub rolled out a new search engine and browser in May 2023, making it possible to find relevant results at reasonable speed. Knowing the GitHub search syntax helps.

Interoperability

Using GitHub tools exclusively makes it easier to link and automate across your project artefacts. Hence it makes it easier to track, review and deploy changes as well as collaborate with your team and users.

Standardisation

Treating project deliverables as code means you can leverage the same practices that are applied to software development: version control, automation, reusability and maintainability. This results in improved standardisation and quality across your projects and enterprise.

Cost

Using fewer tools can lead to cost savings. However, this reason may be less significant if other teams in your company do not use GitHub and are unlikely to switch.

Everything?!

Well not actually everything:

- GitHub limits the size of files allowed in repositories. Moreover, Git isn’t great for storing binary files which are not diffable. Instead, you should store large and binary files in a dedicated file store like Git LFS

- Although GitHub Secrets can securely store credentials and is great for personal projects, it’s not designed to be a comprehensive secret management tool – instead, consider using an infrastructure-based solution such as AWS Secrets Manager or Microsoft Azure Key Vault

This still leaves many other features that can be effectively incorporated into GitHub.

Automation

GitHub Actions automates software workflows, allowing users to build, test, and deploy code directly from their GitHub repositories. Since its release in 2019, it has become the preferred CI tool for personal projects. GitHub Actions’ popularity corroborates the integrated approach advocated in this post. It also helps that the YAML configuration is user-friendly, and that the GitHub Marketplace offers a vibrant and growing ecosystem with a wide range of pre-built actions.

Due to limited support for complex workflows, industry adoption has been more gradual. Uptake will accelerate as more capabilities are added, such as Job Summaries and GitHub Actions Importer. As validation, in 2023 Thoughtworks upgraded the GitHub Actions rating from Trial to Adopt.

Project management

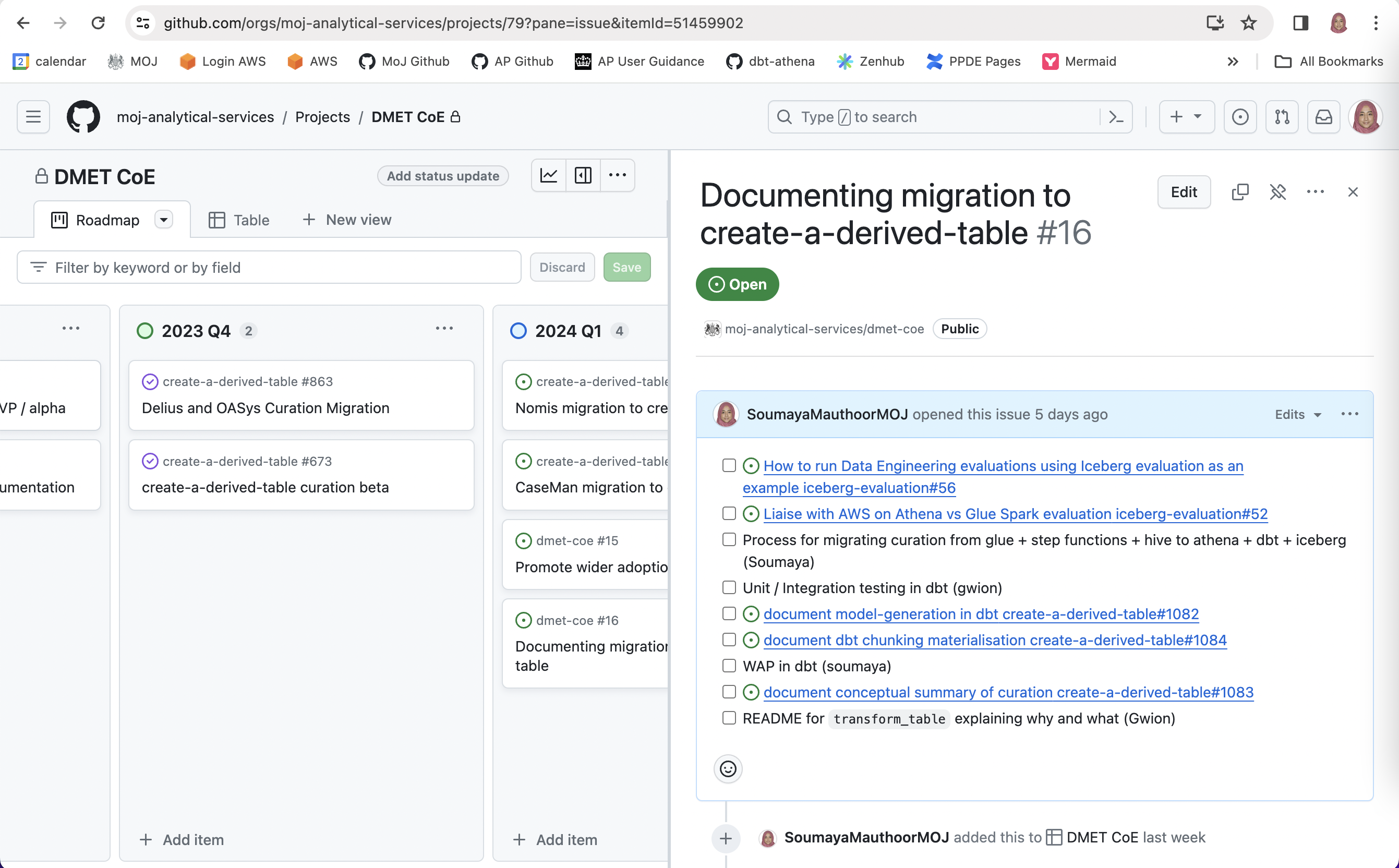

The classic version of GitHub Projects, launched in 2016, is an infamous example of releasing a product too early. It consisted primarily of a Kanban board and lacked basic features such as a backlog view, deterring most enterprise users. In August 2022, GitHub released a revamped version of GitHub Projects, which offers a more intuitive, flexible, and customisable user interface.

Users can now plan and track work using either a table or board view. Projects are created at the GitHub organisation level, making them linkable to repositories but independent from them. Additionally, you can incorporate issues from other GitHub organisations, although there won’t be a reciprocal link from the issue to the project. There are various ways to automate projects. The simplest are the built-in automations, which, for example, can update the status of an issue to ‘Done’ when it is closed.

Epics

Epics are often used to structure agile backlogs and to break down large issues into more manageable work. GitHub offers three options for managing epics.

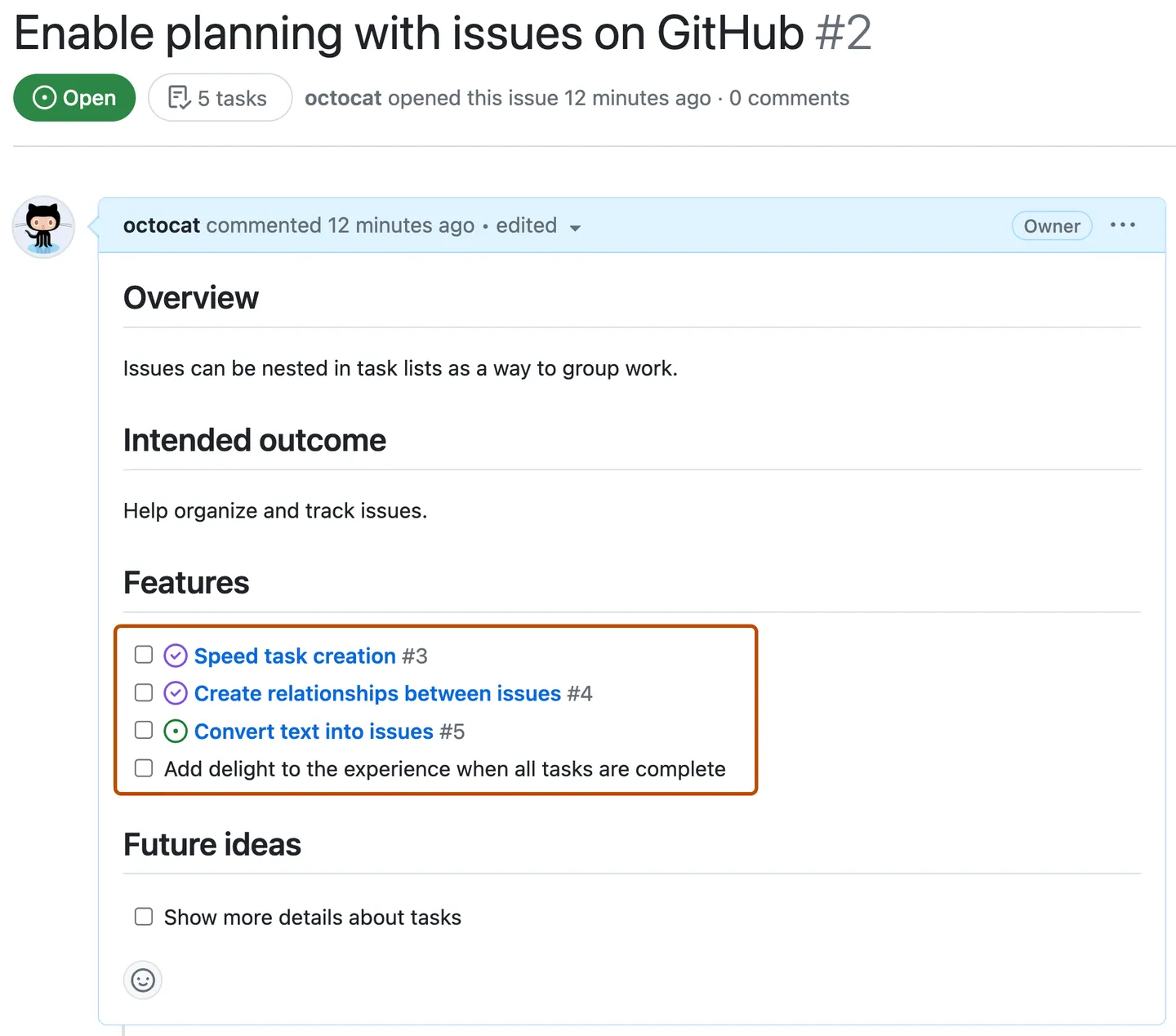

1. Task lists

Task lists have been around since 2014. GitHub is currently working on a significant upgrade, which is still in private beta, so stay tuned for updates!

You can link to issues, pull requests and discussions within the same repository using the simple #number pattern:

- [x] #739 - [ ] https://github.com/octo-org/octo-repo/issues/740 - [ ] Add delight to the experience when all tasks are complete :tada:

For cross-repository linking, you’ll need to specify the full URL. You can also draft tasks until you’re ready to convert them into issues or leave them as-is for smaller tasks.

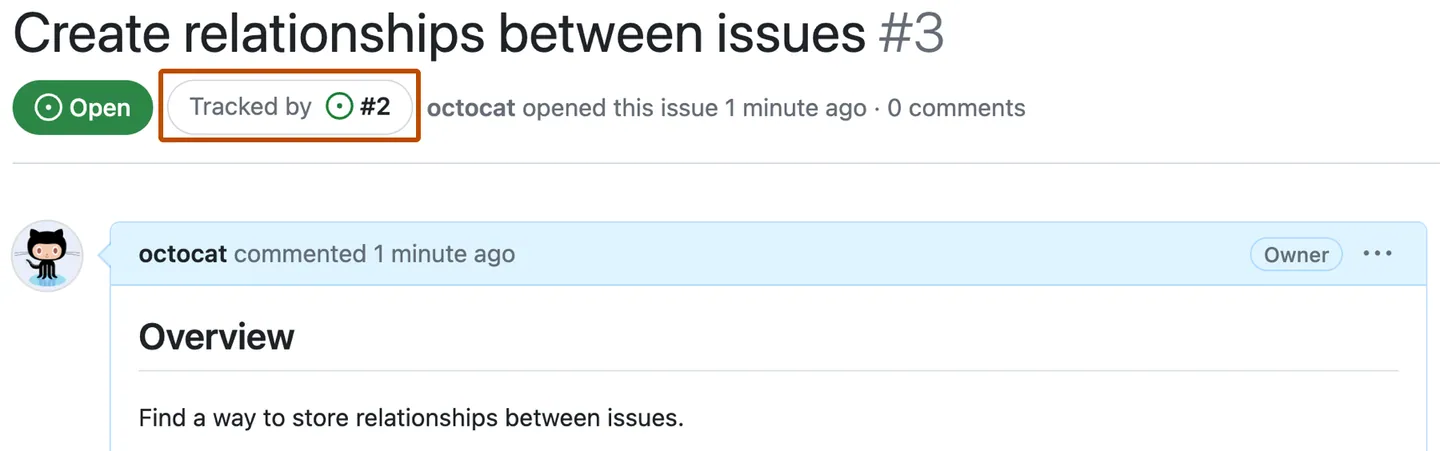

I recommend assigning an ‘Epic’ label to parent issues to make them easier to identify. You can display the ‘Epic’ label in GitHub Projects, and filter and search by the ‘Epic’ label. Although GitHub Projects does not yet display relationships, it’s easy to view by opening the issue screen.

You can navigate back to the epic in the ‘Tracked by’ section next to the child issue’s status.

Navigating back to the epic from discussions and pull requests isn’t as straightforward. As a workaround, you can add the epic to the pull request or discussion description using the format: - Epic: #number. Using a bullet list forces GitHub to render the epic title, improving clarity.

2. Milestones

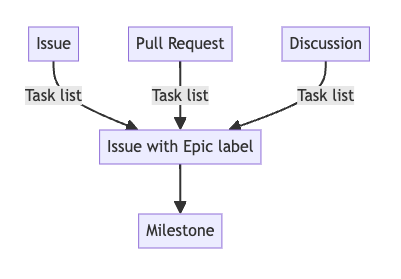

Milestones can be associated with issues and pull requests, but not discussions. You can display milestones on GitHub Projects as an additional column, and add them to the GitHub Project roadmap layout. For more complicated projects that require a more nested hierarchy, you can group issue epics into milestones, as explained in this mermaid diagram.

```mermaid

flowchart

Epic[Issue with Epic label]

Issue --> |Task list|Epic

PR[Pull Request] --> |Task list|Epic

Discussion --> |Task list|Epic

Epic --> Milestone

Note that cross-repository milestones are not yet supported. A workaround is to record all issues in a core repository, even if the code is split amongst multiple repositories. This also makes it easier to manage work. You can disable issues in the non-core repositories to enforce this rule.

3. Labels

Don’t use labels for epics! This may seem an obvious option at first, but unlike milestones, you can’t set dates, track completion status or close labels.

Roadmaps

The GitHub Project roadmap layout displays the project items on a timeline. However, I prefer using the board layout and grouping issues by quarter. You can modify the ‘status’ field to store the quarter, as used in the GitHub public roadmap. Alternatively, you can create a separate ‘quarter’ field.

Using quarters instead of dates encourages product owners and delivery managers to follow good practice such as:

- creating epics that are shorter than a quarter

- limiting the number of epics undertaken per quarter

- giving less precise but more accurate start and completion dates

Requirement analysis

The MoSCoW method is used to prioritise project requirements by splitting them into must-haves, should-haves, could-haves and won’t-haves. This can be done within GitHub Projects by creating a new ‘priority’ field with the relevant labels. The items can start as drafts and later be converted into issues once more fleshed out.

User Acceptance Testing (UAT)

A typical UAT scenario involves migrating a large group of users to a new solution and making sure that existing functionality is replicated. A simple way of tracking progress is through a spreadsheet with a row per user and columns for recording the completion of different actions. Instead, we have successfully used GitHub Projects to track UAT progress. Those internal to MoJ can access this private project for tracking user migration to a new database as an example. For external users, the concept is straightforward:

- Create an issue template to outline the different actions.

- Generate a ticket for each artefact that needs to be migrated.

- Replace the ‘status’ field with the different actions.

- Use the project board layout to track progress.

There are many advantages. You can:

- assign tickets to GitHub user accounts, instead of named individuals

- use a single issue to track progress and communication

- take advantage of GitHub automation

Project documentation

Documentation about your project can take many forms, which needs to be recorded and managed differently depending on the audience and use case.

Documentation about your code

The best place for documentation about your code to reside is in your code. Good code documentation practice is outside the scope of this post. You can refer to this article for some great pointers on documenting Python code.

Documentation about your project

This includes architecture, dependencies, setup instructions and user guidance. You can keep this information in GitHub as Markdown files in your GitHub repository’s /docs folder. An alternative is to use GitHub wikis, as has been successfully achieved by Astro Bookings. However, I would not recommend them for reasons that are best summarised in this article.

GitHub uses a variant of Markdown called GitHub Flavored Markdown. It also uses Liquid syntax to expand the functionality, for example, to provide accessible tables and chunks of reusable content. However, the basics should suffice for most needs.

Whilst it’s recommended for documentation to go through the same review process as code, it can sometimes feel onerous. You can modify the codeowners to skip the approval process for changes to the /docs folder. You can also modify GitHub workflows to skip the workflow, which is useful in the case of long-running tests.

A few things to note about structuring the /docs folder:

- With a monorepo layout, you can split off into multiple

/docsfolders at the root of each sub-folder, but this can make it more complex to manage and navigate. - With a multi-repo approach, you can use the core repository or create a specific documentation repository for storing team or application-level documentation. You can’t combine code and documentation changes made against different repositories in a single pull request, but you can still link them via a task list.

Publishing your documentation

You can convert your documentation into a website using static site generators and host it on GitHub Pages, GitHub’s static site hosting service. For instance, this blog is hosted on GitHub Pages and generated using an Eleventy plugin. GitHub Pages isn’t limited to hosting documentation; we also use it to publish our tech radar.

Documentation about your approach

When you’re evaluating options or completing some analysis you often create transient documentation. This type of documentation should be kept separate from your code to avoid clutter and confusion, especially for new team members. Your /docs folder should reflect the current state of your project, just like your code.

Instead, you can use GitHub Discussions, which was released in August 2021. Discussions are not enabled by default so you’ll have to update the repository settings. If you use a multi-repo approach, you can limit discussions to the core or documentation repository to make it easier to track and search.

Unlike the /docs folder, discussions don’t require approvals. Whilst it simplifies the workflow, it does mean that discussions can become an information swamp. Hence you need a process for transferring sanitised information to the /docs folder. Luckily GitHub Discussions support the same advanced formatting as Markdown pages, which makes it easy to copy and paste. I recommend closing a discussion once the information has been migrated to the /docs folder.

GitHub Discussions allow your users to participate with the idea generation process through comments, reactions and polls. However, this means everyone involved will need to check their GitHub notifications regularly. It can also cause confusion if you already use another communication tool, such as Slack. A good rule of thumb is to consider whether you might want to refer to this information in a year’s time. If so, use a discussion!

Diagrams

Mermaid is a JavaScript-based tool that lets you create diagrams using a Markdown-like syntax. GitHub released support for Mermaid in February 2022. It’s particularly handy for adding editable diagrams to places like issues and discussions, as you don’t have to save it to the /docs folder. However, I found that Mermaid has a steep learning curve and limited options available so I would only suggest it for simple diagrams. Moreover, it’s not natively supported by many static site generators.

Instead, I recommend using Excalidraw, an open-source diagramming and whiteboarding tool. GitHub doesn’t provide native support for Excalidraw, but you can export the diagram to SVG or PNG and embed the Excalidraw scene data to make it editable. Whilst SVG is preferable because it is smaller in size and is text-based (and hence diffable), unfortunately, it doesn’t render as nicely in GitHub so I would stick with PNG for now. You can then upload the image file directly to issues and discussions, or save it to a /docs/images folder for version control. GitHub has a nifty image view mode for reviewing changes to images. You can edit diagrams on the Excalidraw web editor or download the VS Code extension to edit locally. You can also import diagrams directly from GitHub into the web editor by passing in the raw image URL (see my Excalidraw diagram hyperlink as an example). Lastly, Excalidraw plus GitHub Discussions is great for recording the outcome of collaborative whiteboard sessions, which tend to get lost.

Slides

Marp is an open-source ecosystem for creating slide decks in Markdown, which can be exported to various formats, including PDF and HTML. Similar to Excalidraw, GitHub does not provide native support, but you can save the Markdown files in a /docs/slides folder. The marp-to-pages GitHub template repository is great for starting out and includes a GitHub action for exporting to HTML and publishing to GitHub Pages. The VS Code extension makes it easier to edit and preview Markdown files locally.

While there’s a bit of a learning curve, once you’ve decided on a format, it’s very intuitive. We’ve successfully used Marp to create slide decks when evaluating Iceberg. Additionally, I’ve exported the README.md to HTML and hosted it on GitHub Pages for better visibility. Note that you shouldn’t commit generated files, but it’s fine for exploratory projects. For production code, you should use something like the marp-to-pages GitHub action, which generates PDF and HTML files as part of a pull request or merge.

Conclusion

Historically, GitHub has been mainly valued for source code management. Recent enhancements to the GitHub ecosystem, coupled with various open-source tools, make it possible to integrate code, automation, tracking, and documentation within one platform. Whilst it may not work in all circumstances, we’ve found this setup beneficial, leading to increased efficiency, consistency, and transparency.

If you have any comments or suggestions please post on the discussion.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the following people and resources:

- The managed pipelines crew for being so open to experimenting!

- The Saturday Coding Club for providing insightful suggestions

- Richard Baguley for introducing me to Excalidraw

- Julia Lawrence for encouraging me to give GitHub Projects another try

- Calum Barnett for making sure I follow the GDS style guide

- ChatGPT3.5 for proofreading and adding a touch of polish